REVIEWS & ARTICLES February 2025

ARCHIVE

Living Inside of a Painting, Gazing Out Upon the World

Commentary by Mark Waldman

Each month, when you walk into the Blackboard Gallery, where our writers group meets on the first Wednesday of each month, you are surrounded by a new collection of extraordinary art, featuring invitational solo shows, juried group shows, and themed exhibitions. It’s an ideal prompt for producing poetry and prose.

But does the art “speak” to you? I mean this literally. And do you know how to listen to a piece of visual art in a way that inspires you to write? There’s a field of research called neuroaesthetics, and the studies consistently show that most people barely glance at a painting or sculpture in a museum or gallery because they have not trained themselves to step out of the habitual ways that we have learned to look at the world.

The brain, you see, only wants to pay attention to about 7-11 small areas, just enough to make sense out of what is being represented: a landscape, or portrait, or a familiar object. But when it comes to abstract art, a person needs to train themselves to look at it differently, to suspend preconceptions and gut-level reactions. To really appreciate a work of art, the viewer needs to seek out its aesthetic appeal which turns out to be a highly complex and sophisticated neurological process that includes nearly every network and structure in the brain, areas that are involved in vision, movement, sound, and especially moral values. Thus, any unconscious belief you might have about nature, people, culture, and politics would need to be briefly suspended if you really wanted to experience the totality of a single work of art.

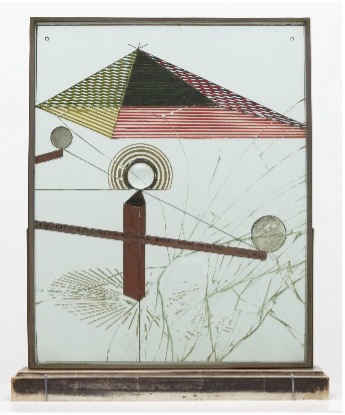

How do you do that? How can you look through different eyes and use different senses that will allow you to more fully immerse yourself in the thousands of subtleties before you? And many artists are particularly aware of how little time a person takes to appreciate what they’ve created. Marcel Duchamp even gave specific instructions on how to look at – or should I say through – the piece he referred to as the little glass:

“To Be Looked at (from the Other Side of the Glass) with One Eye, Close to, for Almost an Hour”

These words are inscribed on a strip of metal that is glued across the center of the composition, and viewers were to look through a lens embedded into it to achieve a hallucinatory effect by seeing the rest of the gallery – and the people in it – upside down. Few people actually spend more than 30 seconds, and I’m willing to bet that few people spend less than a minute looking at most of the pieces in an art show.

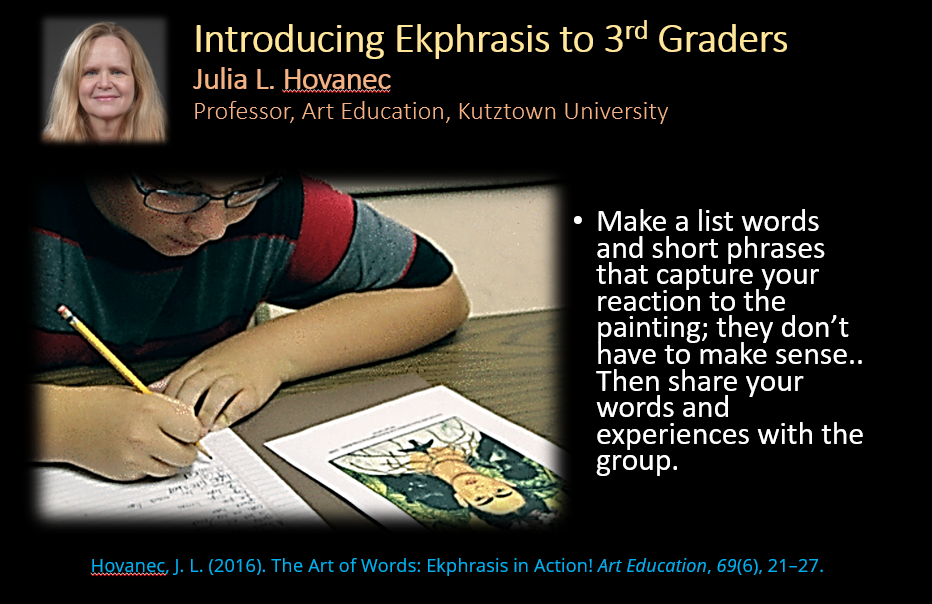

Might there be an easier way, a more playful way, to lose yourself in a painting or sculpture, or any form of visual art? Last month our host, Jennifer Jones, had us pair up with each other, to select an intriguing artwork, and to literally ask it questions about itself. Not only did everyone choose to spend 30-40 minutes conversing with the piece, and then crafting a poem or a short prosaic paragraph, but the number of astonishing insights and experiences that emerged surprised nearly everyone, no matter their degree of artistic expertise. The writings were shown to artists who were deeply touched, and several of them are featured in this month’s Poetry & Prose section.

The experiment was a variation of Jung’s Active Imagination technique, a form of ekphrastic “archetypal writing”. If you scroll down this page, you’ll find written instructions on how to do this exercise with others.

On March 5th, Gerald Zwers will use the new exhibition – combined with unusual sounds and unexpected choices of words – to take us even deeper into new experiential levels of writing and artistic appreciation, tapping into the imagination and creativity networks in the brain that can interrupt our unconscious propensity to turn the extraordinary into the ordinary. reduce everything into familiar objects and definitions. It’s another form of ekphrastic experience.

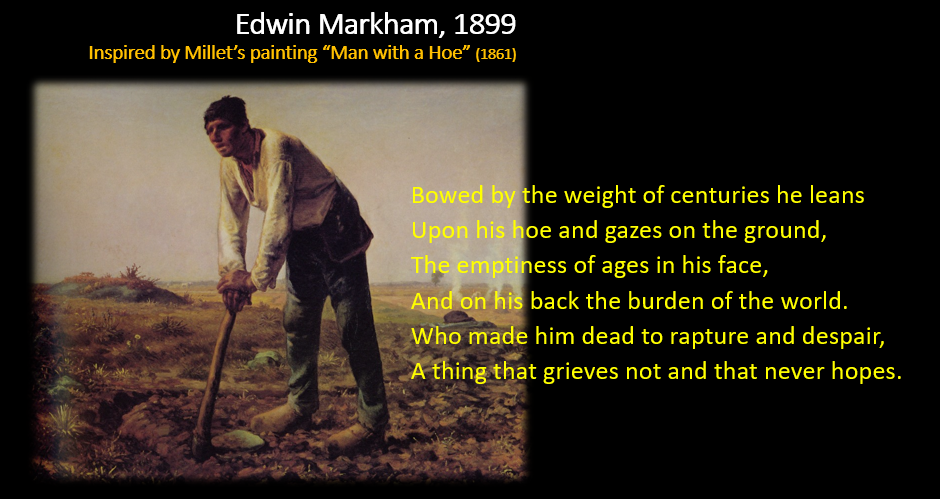

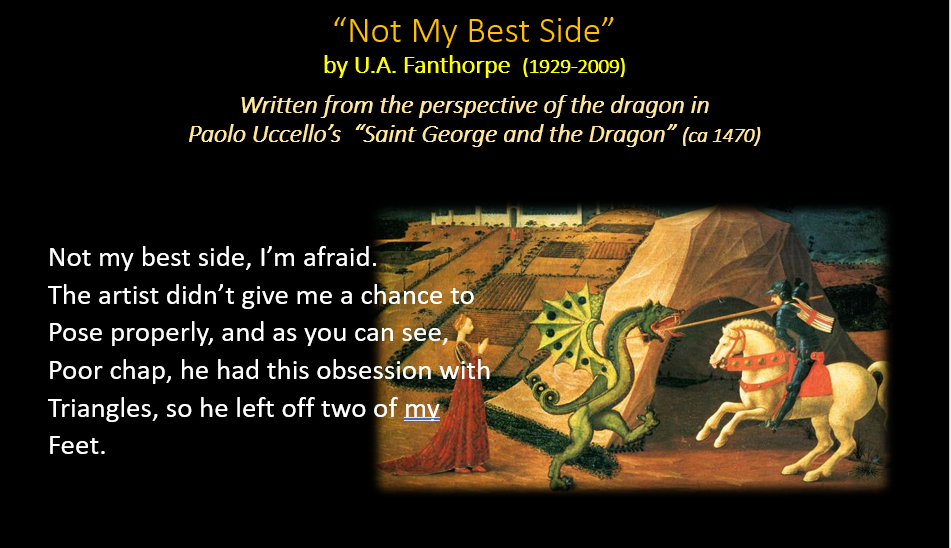

But what, exactly, is ekphrasis? Traditionally, it has been defined as the verbal representation of visual art – an essay, an inspirational poem, etc. – but today it encompasses a wide variety of approaches that overlap each other:

A Brief History of Ekphrastic Writing

Descriptive Ekphrasis: This form involves detailed and vivid descriptions of visual art, aiming to bring the artwork to life through words. It has its roots in ancient Greek rhetorical exercises and has been a staple in literature from classical antiquity to modern times. Often, the goal is to make the reader “see” the artwork through words.

Haptic Ekphrasis: This form, which emerged during the Romantic Period of 18th-19th century literature, emphasizes the sensory and emotional engagement with art, exploring themes of empathy and emotional resonance. A writer, for example, might turn the tactile sensations of a sculpture into words, focusing on its temperature, texture, and weight, or the emotional feelings that are stirred up when running one’s hands over its surface.

Ekphrastic Melopoetics: In this form, ekphrastic writing explores the relationship between musical and poetic rhythm, and how sound patterns can create meaning. Sounds and music might be integrated into the performance of a poem, or serve as a background for a literary reading. Or the writer might express the emotions evoked from a piece of music, or integrate elements of musical rhythm into their work. In the field of neurocognitive poetics, researchers are studying how certain texts evoke musical experiences, how poetic speech affects the listener’s brain, and how certain words and phrases create melodic patterns.

Intermedial Ekphrasis: This form explores the dynamic and fluid relationships between different art forms. It extends beyond poetry into fiction, film, music, and digital art, often integrating writing with sound, visual effects, and tactile sensations. Ekphrasis can become a way to blur boundaries between different forms of art.

Click on the video below to watch a wonderful example of this form created by Phil Taggart, a highly regarded poet and teacher in Ventura County. The piece is called “Market Street” and Phil will be giving a presentation at “Writers in the Gallery” in the near future:

Theatrical Ekphrasis: This approach includes performance poetry, where the writer enacts an artistic experience or creates a participatory experience for the reader.

Today, ekphrastic expression blurs the boundaries between different forms of art. It can be found in experimental prose pieces reacting to installations, films visually echoing sculptures, and even digital art that “responds” to historical artworks in interactive ways. The common thread is the use of language to interpret, engage with, and reimagine another form of art.

Ekphrastic Melopoetics: In this form, ekphrastic writing explores the relationship between musical and poetic rhythm, and how sound patterns can create meaning. Sounds and music might be integrated into the performance of a poem, or serve as a background for a literary reading. Or the writer might express the emotions evoked from a piece of music, or integrate elements of musical rhythm into their work. In the field of neurocognitive poetics, researchers are studying how certain texts evoke musical experiences, how poetic speech affects the listener’s brain, and how certain words and phrases create melodic patterns.